Sclera: The White Of The Eye

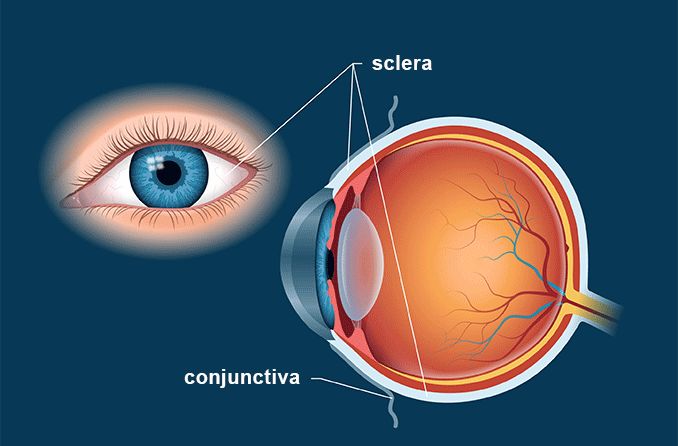

The sclera is the white part of the eye that surrounds the cornea. In fact, the sclera forms more than 80 percent of the surface area of the eyeball, extending from the cornea all the way to the optic nerve, which exits the back of the eye. Only a small portion of the anterior sclera is visible.

Sclera Definition

The sclera is the dense connective tissue of the eyeball that forms the "white" of the eye. It is continuous with the stroma layer of the cornea. The junction between the white sclera and the clear cornea is called the limbus.

The sclera ranges in thickness from about 0.3 millimeter (mm) to 1.0 mm. It is composed of fibrils (small fibers) of collagen that are arranged in irregular and interlacing bundles. The random arrangement and interweaving of these connective tissue fibers are what account for the strength and flexibility of the eyeball.

The sclera is relatively inactive metabolically and has only a limited blood supply. Some blood vessels pass through the sclera to other tissues, but the sclera itself is considered avascular (lacking blood vessels).

Some of the nourishment of the sclera comes from the blood vessels in the episclera, which is a thin, loose connective tissue layer that lies on top of the sclera and under the transparent conjunctiva that covers the sclera and episclera. Larger episcleral blood vessels are visible through the conjunctiva.

Other nourishment of the sclera comes from the underlying choroid, which is the vascular layer of the eyeball that is sandwiched between the sclera and the retina.

Sclera Function

The sclera, along with the intraocular pressure (IOP) of the eye, maintains the shape of the eyeball.

The tough, fibrous nature of the sclera also protects the eye from serious damage — such as laceration or rupture — from external trauma.

The sclera also provides a sturdy attachment for the extraocular muscles that control the movement of the eyes.

READ NEXT: Staphyloma

Sclera Problems

Here are a few conditions that can affect the sclera:

Scleral icterus (yellow eyes). This condition — also called icteric sclera — is a yellowing of the white of the eye. It is associated with hepatitis and other liver disease.

There is some controversy about the accuracy of the name of this condition. Some researchers have stated that the yellowing of the eyes (jaundice) actually takes place in the conjunctiva, not the sclera itself, and that the condition should therefore be called conjunctival icterus instead. Despite this, many doctors continue to call yellow eyes or yellowing of the eyes "scleral icterus" because it's the color of the underlying white sclera that is altered by the condition.

Increased blood serum levels of bilirubin (an orange-yellow pigment formed in the liver) is commonly associated with scleral icterus. If you develop yellow eyes, you should have blood tests to see if you have this condition and associated liver problems.

Blue sclera. As you would expect, this condition is when a normally white sclera has a somewhat blue color. Blue sclera is caused by a congenitally thinner-than-normal sclera or a thinning of the sclera from disease, which allows the color of the underlying choroidal tissue to show through it.

Congenital and hereditary diseases associated with blue sclera include osteogenesis imperfecta (brittle bone disease) and Marfan's syndrome (a connective tissue disorder). Acquired diseases such as iron deficiency anemia also can be associated with blue sclera.

READ NEXT: What Is Ochronosis

Episcleritis. This is inflammation of the episclera that lies atop the sclera and under the conjunctiva. Episcleritis is relatively common and tends to be benign and self-limiting. It has two forms: nodular episcleritis where the redness and inflamed tissue occurs on a discrete, elevated area overlying the sclera, and simple episcleritis, where dilated episcleral blood vessels occur without the presence of a nodule.

The cause of most cases of episcleritis is unknown, but a significant minority (up to 36 percent) of people who get the eye condition have an associated systemic disorder — such as rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, lupus, rosacea, gout and others. Certain eye infections also may be associated with episcleritis.

Most episodes of episcleritis will resolve on their own within two to three weeks. Oral pain medication and refrigerated artificial tears may be recommended if discomfort is a problem.

Scleritis. This is inflammation of both the episclera and the underlying sclera itself. Scleritis is a more serious and typically more painful red eye than episcleritis. Up to 50 percent of cases of scleritis involve an underlying systemic disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis.

Generally, the onset of scleritis is gradual, and most patients develop severe, piercing eye pain over several days. This pain tends to worsen with eye movements. In most cases, the inflammation begins in one area and spreads until the entire sclera is involved.

Scleritis can cause permanent damage to the eye and vision loss. Frequent complications include inflammation of the cornea (keratitis), uveitis, cataract and glaucoma.

Scleritis typically is treated with oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and corticosteroids. In some cases, immunomodulatory therapy may also be prescribed. Scleritis may remain active for several months or even years before going into long-term remission.

SEE RELATED: Anterior Uveitis

What Is A Scleral Buckle?

A scleral buckle is not a condition of the sclera — it's the name of a surgical procedure used to repair or prevent a detached retina.

In the scleral buckle procedure, a band of silicone, rubber or semi-hard plastic is generally placed around the mid- to posterior sclera and sutured in place. This band pushes in, or "buckles," the sclera inward, toward the detached or torn retina, allowing the loose retinal tissue to rest against the inner wall of the eye.

The retinal surgeon then uses either extreme cold (cryopexy) or a specific band of focused light (laser photocoagulation) to seal the retinal tissue against the wall of the eyeball, repairing the torn or detached retina.

A scleral buckle usually is left in place permanently.

READ MORE: Eyeball Piercing

Episcleritis. EyeWiki. American Academy of Ophthalmology. August 2016.

Scleritis. EyeWiki. American Academy of Ophthalmology. December 2015.

Remington, Lee Ann. Clinical Anatomy And Physiology Of The Visual System, 3rd Edition. Butterworth-Heinemann, 2012.

Cassel GH, Billig MD, and Randall, HG. The Eye Book: A Complete Guide To Eye Disorders And Health. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

'Conjunctival icterus,' not 'scleral icterus'. JAMA (Journal of the American Medical Association). December 1979.

Page published on Wednesday, February 27, 2019