Vision problems of school-age children

Your child's vision is essential to his success in school. When his vision suffers, chances are his schoolwork does, too.

Vision problems are common among school-age kids. According to Prevent Blindness America, one in four school-age children have vision problems that, if left untreated, can affect learning ability, personality and adjustment in school.

School-age children also spend a lot of time in recreational activities that require good vision. After-school team sports or playing in the backyard aren't as fun if you can't see well.

Warning Signs Of Vision Problems In Kids

Refractive errors are the most common cause of vision problems among school-age children. Parents, as well as teachers, should be aware of these 10 signs that a child's vision needs correction:

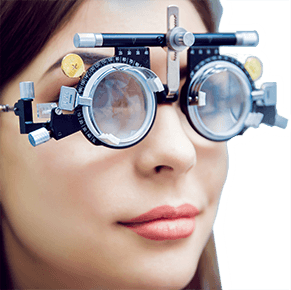

Blurry vision may be interfering with your child's ability to learn in school. Regular eye exams can detect and correct this and other vision problems.

Consistently sitting too close to the TV or holding a book too close

Losing his place while reading or using a finger to guide his eyes when reading

Squinting or tilting the head to see better

Frequent eye rubbing

Sensitivity to light and/or excessive tearing

Closing one eye to read, watch TV or see better

Avoiding activities which require near vision, such as reading or homework, or distance vision, such as participating in sports or other recreational activities

Complaining of headaches or tired eyes

Receiving lower grades than usual

Schedule an appointment with an optometrist or ophthalmologist if your child exhibits any of these signs. A visit with the doctor may reveal that your child has myopia (nearsightedness), hyperopia (farsightedness) or astigmatism. These common refractive errors are easily corrected with eyeglasses or contact lenses.

FIND A DOCTOR: Don't let poor vision affect your child's life. Find an eye doctor near you for an appointment.

Learning Disabilities

Learning disabilities (LD) are another concern with school-age children. According to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, learning disorders affect at least 1 in 10 schoolchildren.

Learning disabilities are psychological disorders that affect learning; they are not vision problems. But learning-related vision problems sometimes can coexist with LD or be associated with learning disabilities.

In fact, a recent study conducted by researchers at Mayo Clinic found that children with binocular vision problems (intermittent exotropia and convergence insufficiency) were significantly more likely to be diagnosed with learning disabilities and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) than children with normal eye alignment.

If your child frequently reverses letters while reading or writing, exhibits poor handwriting, dislikes or has difficulty with reading, writing or math, consistently mistakes his left for his right or vice versa, can't verbally express himself or consistently behaves inappropriately in social situations, then seek help.

A multidisciplinary approach usually is the best way to find the cause of learning problems. Consultation with your child's teacher should be the first step. But it's wise also to consult with an eye doctor who specializes in eye exams for children and your pediatrician for additional advice and possible referral to specialists.

Eye Exams: How Often?

According to the American Optometric Association, children should have an eye exam by no later than 6 months old, then again by age 3 years, and just before starting school.

School-age children need an exam every two years after that if they have no visual problems. But if your child requires eyeglasses or contact lenses, schedule visits every 12 months.

Frequent eye exams are important because during the school years your child's eyeglasses prescription can change frequently.

Your eye care practitioner also will ensure that your child has the visual skills required for success in school and sports, such as accurate and comfortable eye teaming, peripheral vision, ease of focusing from distance to near and hand-eye coordination.

The Problem With Vision Screenings

Keep in mind that a vision screening performed by your pediatrician or the school nurse is not a comprehensive eye exam. These screenings are designed to alert parents to the possibility of a visual problem, but not take the place of a visit to an eye care practitioner.

Vision screenings are helpful, but they can miss serious vision problems that your eye care practitioner would catch. A child who can see the 20/20 line on a visual acuity chart can still have vision problems, and the visual skills needed for reading and learning are much more complex than identifying letters on a wall chart.

Also, children who fail vision screenings often don't get the vision care they need. Two studies published by the American Academy of Ophthalmology found that 40 to 67 percent of children who fail a vision screening do not receive the recommended follow-up care by an eye doctor.

One reason for this lack of compliance is poor communication with parents who may or may not be present at the screening. One study found that two months later, 50 percent of parents were unaware their child had failed a vision screening.

The best way to make sure your child has the visual skills he needs to excel in and outside the classroom is to schedule routine comprehensive eye exams with an eye doctor who specializes in children's vision.

Eye News

The Eyes May Reveal Depression Risk In Children

We all know that the eye's pupil reacts to light, dilating in dim light and contracting when it's bright. Researchers have been finding that the pupil can react differently to various types of images as well, serving as a biomarker for emotional and mental states.

According to a study by scientists at Binghamton University, how children's pupils react to sad faces can help determine their risk of developing depression over the next two years.

The researchers measured the pupils of children of depressed mothers while they viewed angry, happy and sad faces on a screen. The pupillometry was performed with an eye-tracking device. For two years afterward the children were assessed for depressive symptoms. Those with relatively greater pupil dilation when viewing sad faces tended to have higher levels of symptoms and to have a clinically significant depressive episode earlier after the screen test.

Since pupillometry is inexpensive, this assessment method could potentially be in widespread use by pediatricians and eye doctors.

School-aged vision: 6 to 18 years of age. American Optometric Association. www.aoa.org. Accessed April 2017.

Pupillary reactivity to sad stimuli as a biomarker of depression risk: evidence from a prospective study of children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. July 2015.

Facts for families: children with learning disorders. American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. August 2013.

Mental illness in young adults who had strabismus as children. Pediatrics. November 2008.

Insights on the efficacy of vision examinations and vision screenings for children first entering school. Journal of Behavioral Optometry, September/October 2003.

Preschool vision screening in pediatric practice: A study from the Pediatric Research in Office Settings (PROS) network. Pediatrics. May 1992.

Page published on Friday, January 24, 2020